Hammering a rolling bearing during mounting, especially with point contact, causes damage due to the delicate internal design and extremely high contact stresses involved. Let’s break it down technically and visually:

Why It Damages the Bearing

- 1. Point Load Overstress

Rolling bearings are designed to handle distributed loads through rolling elements (balls or rollers), not sharp impulse forces.

- A hammer hit introduces a highly concentrated force at one location (point contact), far exceeding material yield limits in that tiny area.

Result:

Micro-cracks, indentations (brinelling), and even raceway deformations.

2. False Brinelling and True Brinelling

- If the hit is on a static bearing, it may leave permanent dimples where balls press into the race.

- This destroys the smoothness of the raceway → vibration, noise, and premature failure.

3. Internal Misalignment

- Hammering on one ring (usually the outer) causes impact force to travel through the rolling elements to the opposite ring.

- This misaligns the inner ring vs. outer ring and may cause fractures in cages or rollers.

4. Surface Hardness Breakdown

- Bearing raceways and balls are precision-ground and heat-treated (often >60 HRC). These surfaces are brittle on purpose.

- A hammer hit introduces plastic deformation → destroys heat-treated layer → early spalling.

5. Cage Deformation or Fracture

- Cages are thin and designed only to guide balls or rollers—not absorb axial impact.

- Hammering can break or deform cages → misrouting of rolling elements → catastrophic failure.

Best Practice Instead

- Use a bearing heater (induction or hot plate) to expand the inner ring thermally, then slide it onto the shaft.

- Or use a bearing mounting tool set that applies force evenly to the ring being mounted (inner ring for shaft, outer ring for housing).

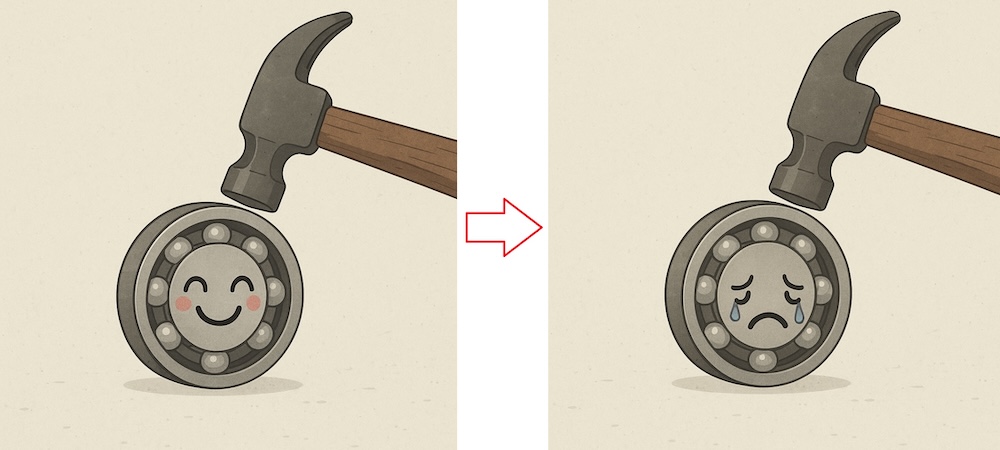

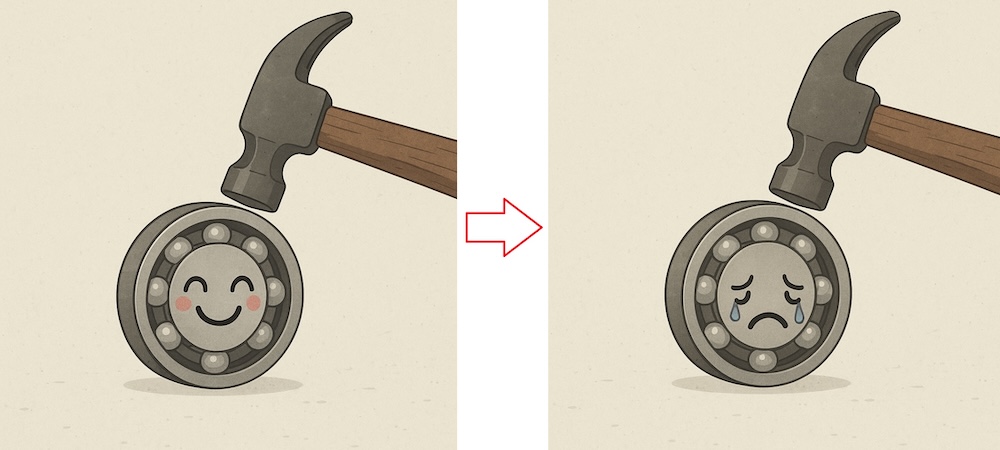

Image (Crying Bearing)

The artwork perfectly shows:

- Left: Happy bearing waiting to be properly installed.

- Right: Damaged and sad after being hammered — symbolizing internal pain no one sees until failure.

Summary

Never hammer bearings into place. Even one improper blow may cut the bearing life to a fraction — from 50,000 hours to 500 hours — and result in unexpected breakdowns in critical machinery.